Why you need to act on Modern Slavery

Introduction

As large entities in Australia are preparing their first modern slavery statements under the Commonwealth Modern Slavery Act 2018 (referred to in this blog as ‘the Act’), it is timely to reconsider the purpose of this Act. Most people are probably aware of instances of modern slavery in supply chains, such as fashion and textiles, where child labour is prevalent and women are at higher risk. Lesser-known might be the spread of modern slavery across industry sectors or the incidence of modern slavery in Australia itself. Even the use of the term itself has been debated in international spheres; however, the implementation of the Act has entrenched its use in Australia.

At the heart of it all is reducing the risk of harm to people, whether in Australia, the Asia-Pacific region or further abroad. Current indications are that almost every supply chain will have modern slavery in it, at the intersections of vulnerable people and business (or supply and demand). The implementation of the Act is a progressive step towards recognising human rights, increasing transparency of slavery practices, and using the leverage of the entity to positively impact on those affected.

Modern slavery, an umbrella term

The term modern slavery has been adopted in Australia to refer to a range of exploitative crimes and activities. It is also used by advocacy groups to raise awareness and campaign for greater transparency in global supply chains. While commentators have discussed the efficacy of the term modern slavery, the Act and guidance for complying with the act (Commonwealth Modern Slavery Act 2018, Guidance for Reporting Entities), list what practices modern slavery can include:

human trafficking

slavery

servitude

forced labour

debt bondage

forced marriage

the worst forms of child labour

The Act includes practices that are offences under the criminal code but “does not include practices like substandard working conditions or underpayment of workers, though these practices are also harmful and may be present in some situations of modern slavery” (https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/criminal-justice/Pages/modern-slavery.aspx)

Policy approaches to reducing global exploitation

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UN Guiding Principles) articulate the corporate responsibility to respect human rights. The Australian Government guidance for reporting entities under the Act refers to these principles and states that entities have a responsibility to respect human rights in their operations and supply chains.

Elsewhere in the sustainability reporting realm, GRI (the Global Reporting Initiative) has included human rights in the Exposure Draft of their Universal Standards – to align with the expectation of responsible business conduct as outlined in the UN Guiding Principles. ‘Modern slavery’ is also included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

Goal 8 is to: promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all

Target 8.7 is to: take immediate and effective methods to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms.

This target has given rise to Alliance 8.7, and its knowledge platform Delta 8.7.

The Act has emerged from this global ambition to combat slavery practices in Australian operations and supply chains. It applies to Australian corporations and other entities with annual consolidated revenue of at least AU$100 million (reporting entities) and requires them to publicly report on risks of modern slavery in their operations.

Reporting periods commenced 2019 with statements due six months after the end of a reporting period, although the submission dates have been temporarily extended this year in response to COVID-19. This initiative provides transparency for public and investor scrutiny (of all reporting entities) via the Modern Slavery Register, administered by the Australian Border Force.

The Australian Government has recently released its first report on the implementation of the Act. This report highlights the education and awareness-raising outcomes achieved by the government in 2019 through conferences, events and forums, business workshops, responding to direct requests and releasing detailed guidance.

The Australian Government is also required to publish an annual Modern Slavery Statement covering Commonwealth procurement and investment activities. Like other reporting entities, the first statement will cover the 2019-20 Australia financial year.

New South Wales and Tasmania are looking to commence and/or enact modern slavery legislation. NSW’s Act has a lower threshold ($50 million consolidated revenue) and includes the appointment of an Anti-slavery Commissioner.

There are numerous Australian organisations concerned with leading the drive against modern slavery. Prominent are the Walk Free Foundation, which produces the Global Slavery Index (2018 GSI) and the Measure Action Freedom report (2019 MAF) Report, and Anti-Slavery Australia.

How many people does it harm?

With an estimated 40.3 million people in modern slavery, these are not isolated practices but occur around the world, including in many developed countries. Dr Ingrid Landau from the Monash Business School reported that modern slavery is prevalent in Australia’s part of the world (i.e. the Asia Pacific Region).

In Australia itself, the Walk Free Foundation estimates there are 15,000 people in modern slavery today, up from their previous estimate of 4,300 people reported by the Australian Human Rights Law Centre (HRLC) in 2017 and higher than the 1,900 people reported by the Australian Institute of Criminology for the period from 2015 – 2017. These figures illustrate the difficulty of estimating the numbers of people affected but may also reflect changes in methodology and scope.

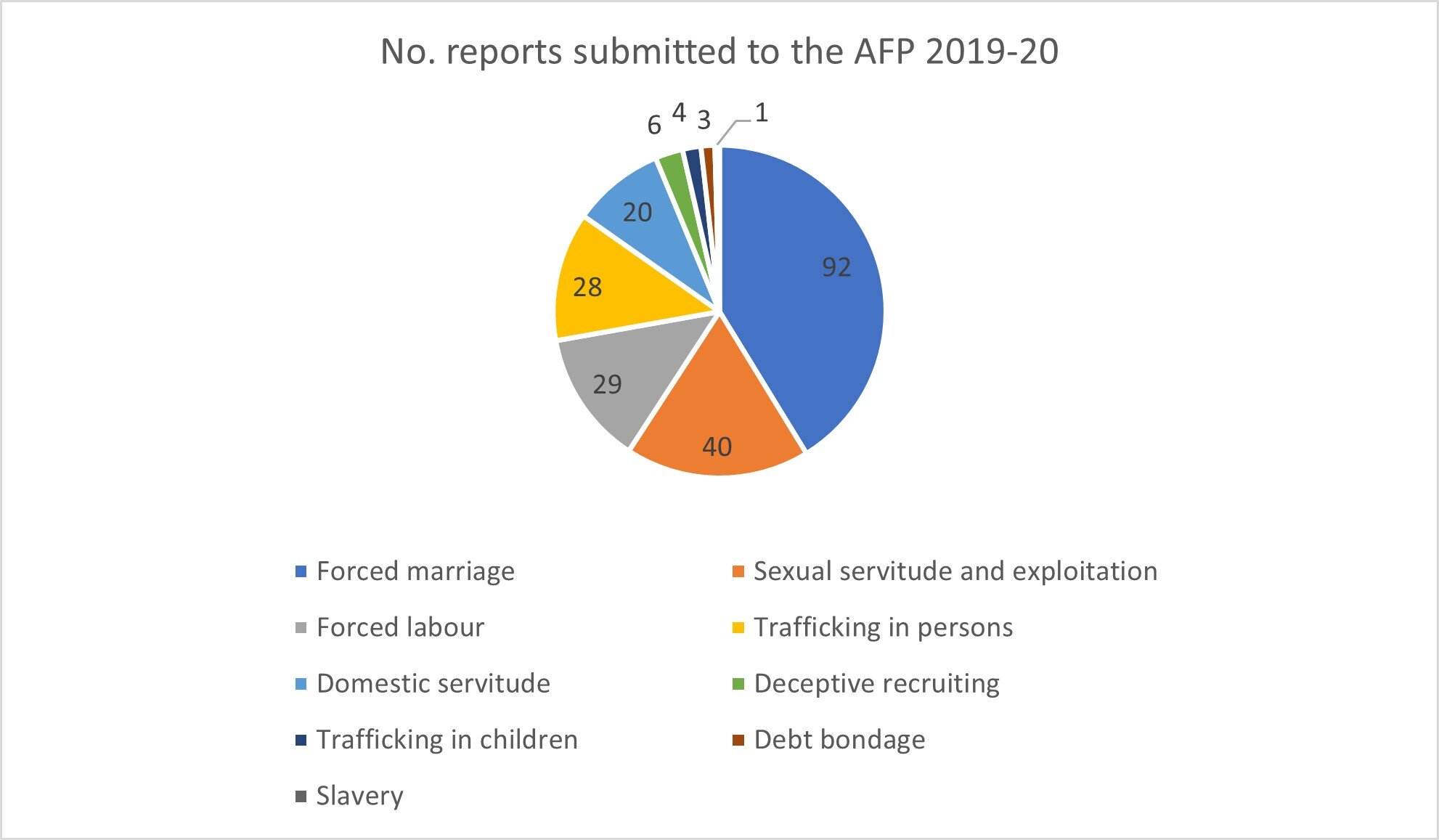

At a granular level, the Australian Federal Police received 223 reports of human trafficking and related activities (which fall under the umbrella term of modern slavery) in the 2019-20 financial year. This provides a snapshot of the types of activities occurring in Australia and is shown in the figure below.

Underlying root causes

Supply and demand in the system

Understanding the root causes of modern slavery requires accepting that exploitation is structural and binary in nature, i.e. some people are vulnerable to exploitation because of their background and circumstances, and others are not. In this sense, the umbrella term works well, since it covers a range of crimes or exploitative activities, which may also include features of another (e.g. a situation of forced marriage, may include forced domestic servitude).

The highest risk for reporting entities under the Act is likely to be forced labour, which was the third-highest reporting category to the AFP after forced marriage and sexual servitude. LeBaron et al. (2018) provide an overview of the root causes of modern slavery, which they describe as the supply and demand sides of the (forced labour) system:

Supply:

poverty – deprivation of material and resources

identity and discrimination – denial to some people of rights and status

limited labour protections – unprotected workers outside the remit of state safeguards

restrictive mobility regimes.

Demand:

concentrated corporate power and ownership – creates downward pressure on working conditions

outsourcing – fragments responsibility for labour standards

irresponsible sourcing practices – heavy cost and time pressures on suppliers

governance gaps – around and within supply chains.

Anti-Slavery Australia expands the ‘supply’ side to include civil disruption and armed conflict, and natural disasters (which in turn link to restrictive mobility) and weak rule of law and impunity. Similar risk factors are reported by Alliance 8.7 in its 2019 report on Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains:

gaps in statutory legislation, enforcement, and access to justice

socio-economic pressures facing individuals and workers

business conduct and business environment

lack of business awareness and capacity

economic and commercial pressures.

These possible causes and risk factors are corroborated by the Australian government in their information sheet on modern slavery and the coronavirus, which acknowledges the increased risk to vulnerable workers because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Australian Border Force (ABF) states “Factory shutdowns, order cancellations, workforce reductions and sudden changes to supply chain structures can disproportionately affect some workers and increase their exposure to modern slavery and other forms of exploitation”. Among the reasons stated are “loss of income or fear of loss of income, low awareness of workplace rights, requirements to work excessive overtime to cover capacity gaps, increased demand due to supply chain shortages or the inability to safely return to home countries”.

Sectoral risks

Modern slavery “Key Facts and Figures”(ABF) links risks to sectors including cleaning, hospitality, agriculture, textiles production and some types of manufacturing. Key risk factors include low skilled labour and outsourcing.

Key sectors are also shown in a graph produced by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and Walk Free Foundation, in partnership with the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in the 2017 report Global estimates of modern slavery: Forced labour and forced marriage (see figure below). Garment making (particularly in South Asian countries), which has attracted a lot of attention from the media, advocacy organisations, and civil society, is included under manufacturing.

Recently (August 2020), the Australian Human Rights Commission and KPMG Australia released the first of five industry-specific guides to help Australian businesses combat modern slavery – Property, Construction and Modern Slavery: Practical responses to managing risk to people. Guides for the health, food, beverage, and finance sectors are in development.

Modern slavery risks may also be linked to certain products, such as rubber products, bricks and construction materials, minerals, cocoa, and tea. The Global Slavery Index provides a list of the top 15 products imported by G20 countries that have a high risk of modern slavery.

Country risks

Modern slavery risks will vary according to country and the sectors/products prevalent in that country. The MAF (2019) report has evaluated country risks according to five milestones: (1) support for survivors (2) criminal justice mechanisms (3) coordination and accountability (4) addressing risk factors (5) stop sourcing goods and services produced by forced labour. The full list covering 183 countries is provided in the report.

Leveraging for change

Commitment

The Act requires Commonwealth and Australian reporting entities to identify and mitigate high-risk activities that may exploit and harm vulnerable persons and to report publicly on these actions. The intent recognises that entities are probably on the demand side of the problem and therefore need to understand why human rights are important and collaborate to find solutions.

The Act requires that statements be approved by the principal governing body of the reporting entity and signed by a member of that body. For companies, this means statements must be approved by the board and signed by a director to provide accountability.

Voluntary reports may also be prepared and submitted to the Modern Slavery Register, but this is a large commitment. An alternative is to prepare a report for publishing on a website or inclusion in corporate sustainability reporting or impact reporting.

Policies and procedures

All organisations should familiarise with the UN Guiding Principles for Responsible Business Conduct (“Protect, Respect and Remedy” framework), specifically The Corporate Responsibility to Protect Human Rights and embed these principles in policy, management systems and procedures. The process of human rights due diligence is to assess actual and potential human rights impacts, integrate and act upon the findings, track responses and communicate how impacts are addressed.

It is clear the requirements of the Act are guided by these principles.

For reporting entities, or those seeking to prepare a statement voluntarily, and with the goal to reduce harm to people in operations and in the supply chain, considerations include:

refreshing policies – such as equity and discrimination, work health and safety, purchasing and procurement, outsourced labour, sexual harassment and assault, grievance, whistleblower policy, training and development

building on existing management frameworks – such as risk assessment and management, safety management, quality management

integrating anti-slavery initiatives in procedures – such as the use of social criteria in purchasing and procurement to screen, inform and build relationships with suppliers

ensuring compliance with the Act – aided by government guidance, tools, and resources – including the Modern Slavery Statement to be submitted by the Commonwealth and reference to statements provided in other Modern Slavery Registers.

Due diligence

The process of human rights due diligence is described above. While these steps are covered by the Act, it is not prescriptive about how risks are assessed or what tier to dive down to in the supply chain, for example. It is important though to make sure the reporting entity (or any entity it owns or controls) considers how it may cause, contribute to, or be directly linked to modern slavery. If not adequately addressed, modern slavery can pose substantial reputational and legal risks for and damage commercial relationships.

Given the complexity of the global system, it is prudent to focus on high risks first, e.g. does the product, sector, or location carry a high risk of slavery? Then delving deeper into these supply chains. Quantifying spend presents both a measure of risk and of opportunity for leveraging change.

An integrated systems approach is required. For example, it might be necessary to review broader performance indicators to ensure they do not inadvertently contribute to modern slavery risks, such as securing fast production times or lowest price. Ethical sourcing and sustainable/responsible supply chains may only be part of the solution.

Continuous improvement

The prevention, mitigation, and remediation of modern slavery in an entity’s operations and supply chains is complex and challenging. It is not expected that organisations certify their activities are slavery-free, and there is no requirement to identify all suppliers by name. It is important that risks are continuously reviewed as the organisation evolves, which is demonstrated by the requirement of the Act to submit annual statements, and capability is built over time.

Other key aspects of an effective program include building relationships with all stakeholders, particularly suppliers, and implementing workplace training and education. The Commonwealth government, for example, rolled out an extensive education program in 2019/20 as outlined in their Implementation Report. Continuous improvement is embedded in the Act itself, which is subject to a three year review period.

Transparent futures

The Commonwealth Modern Slavery Act 2018 has been described as a ‘Do No Harm’ standard. Over time, it might be possible to see what strategies are most effective in leveraging and implementing change.

As listed in the guidance, you do not need to list all risks in your description of potential or actual modern slavery practices or identify all your suppliers or investment holdings by name. “However, you must include sufficient detail to clearly show the types of products and services in the entity’s operations and supply chains that involve risks of modern slavery”. The reporting entity must also describe the actions taken to address risks, including due diligence and remediation processes, how they assess the effectiveness of such actions and consultation processes.

The Commonwealth government’s scoping paper provides an outline of how this might be approached. This includes the intention to develop responses to modern slavery in public sector supply chains that prioritise the best interests of survivors. The priority risk areas for the Commonwealth will include textiles procurement, construction, cleaning services and investment activity.

Entities can also read Modern Slavery Statements produced in the UK, Australia and Canada here – www.modernslaveryregistry.org.

Conclusion

This is an opportunity to build overall capability and promote a culture of fair trade and mutual growth, seeking to look beyond compliance to strategic and meaningful forms of social innovation. Opportunities include developing partnerships between industry, government, civil suppliers and advocacy organisations, as well as championing social protections and labour laws which prevent the sourcing of goods and services produced by forced labour.

——————————————————————————————————————-

By Shelley Anderson, a certified Environment Practitioner and Sustainability professional with experience in Australia and the UK. Her expertise includes sustainability reporting, environmental risk assessment and management, and due diligence, across a broad range of market sectors. Shelley adds great value to the iSystain consultants and design team through her research and consultacy services. She was also a Director of the Cotswold Canals Trust (UK) where she applied her skills to charity governance and impact.

——————————————————————————————————————-

Interested in learning how the iSystain platform can support your compliance with the Modern Slavery Act? Get in touch with us here or contact your iSystain Representative directly.