Destination Net Zero Emissions

The catch cry post Covid-19 is ‘Building Back Better’. There are many aspects to this ambition but systems thinking recognises that responding to climate change, including building on the emission reductions achieved by restrictions during the pandemic, is part of the solution. In order to 'Build Back Better', Australia must act on its pledge to achieve its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement and in addition, seek to attain net zero carbon by the middle of this century.

Australia has the innovative skills and technology to transition to low carbon technologies and sustainable business practices that enhance our environment and build a healthy society. Opportunities for renewable energy, better buildings, manufacturing & mining, transport, resource recovery, land use, education training & research and zero carbon communities were showcased in the recently released (June 2020) Beyond Zero Emissions (BZE) The Million Jobs Plan: A unique opportunity to demonstrate the growth and employment potential of investing in a low carbon economy.

Every element of society has a role to play, but key to sustainable development and positive climate action is the use of carbon accounting and disclosure to disrupt the rise of global surface temperatures. To help Australia meet its carbon reduction targets, the government has mandated the NGER Scheme for corporations that meet set thresholds for greenhouse gases. Protocols have also been developed to enable non-mandated corporations to demonstrate their climate change action.

Australia’s commitment to the global challenge

Under the Paris Agreement, Australia set an emissions reduction target (or Nationally Determined Contribution, NDC) of 26 – 28% below 2005 levels by 2030.

NDCs are the building block of the Paris Agreement. They are to be reviewed and strengthened every five years and each NDC should be tougher than the last (the ‘ratchet mechanism’). Australia’s mitigation target timeframe is 2030, which means it needs to ‘communicate’ or ‘update’ its NDC.

There has been some criticism of Australia’s performance towards its target, including by the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), which rates Australia’s initial (and current) NDC as insufficient. Further, a report commissioned by CPA Australia stated It is reasonable to assume that Australia’s emissions reduction targets will significantly increase under subsequent NDCs, in order to comply with our commitments as a party to the Paris Agreement.

In the meantime, all states and territories in Australia have adopted a target of net zero emissions by 2050 (ACT by 2045) in keeping with the IPCC’s assessment of what is required to meet the Paris Agreement. Links to further information may be found on the government websites.

State and Territory governments may also set carbon reduction targets. The ACT for example, has set targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels (i.e. 40% by 2020, 50 to 60% by 2025, 65 to 75% by 2030, 90 to 95% by 2040 and 100% by 2045). These targets align with the emission reductions needed to implement the Paris Agreement (advice provided to the ACT government by the ACT Climate Change Council).

The case for organisations’ measurement of carbon/GHG footprint

There are compelling reasons for an organisation to calculate its carbon/GHG footprint. Aside from the long game focused on the future health of the planet, there are potential opportunities and benefits in the short-term including:

1. To meet climate change targets

2. To comply with legislative requirements

3. To assure business practices by using Australian and International standards or globally recognised GHG accounting and disclosure protocols

4. To embed climate change action both in operation and sustainability reporting.

Australia needs to meet its international reporting obligations, including its NDCs, under the Paris Agreement. The primary framework enacted in Australia for reporting and disseminating company information about greenhouse gas emissions, energy production and energy consumption is the National Greenhouse Energy and Reporting (NGER) scheme (discussed below).

Several standards have been developed to ensure consistency of GHG accounting and reporting practices. These standards may be mandated (such as the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (Measurement) Determination 2008) or voluntary such as the AS ISO 14064 series on Greenhouse Gases.

Central to many of these approaches is the concept of disclosure. Some disclosure is provided by the NGER scheme, while others relate to claims of climate neutrality (i.e. Climate Active in Australia), financial risks (i.e. the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure, TCFD), or environmental (including carbon) impacts (e.g. CDP).

All types of disclosures provide transparency for stakeholders, including investors, policy makers, consumers, and manufacturers:

Investors – to manage risk exposure (e.g. risk of stranded assets) and ensure progress on decarbonisation

Policymakers – to maintain a level playing field and avoid unintended consequences, to ensure controlled and fair transition to a low carbon economy

Consumers – to inform innovation for low carbon design and meet increasing demand for sustainable products

Manufacturers – to meet increasing demand for visibility about embodied carbon (e.g. carbon labelling) in the products and services they procure.

Voluntary adherence to these types of standards may be certified by third parties for increased internal and external assurance.

Corporate social responsibility also entails transparency and building stakeholder trust to achieve environmental, social and governance (ESG) goals. Calculating and reporting on carbon/GHG emissions and management is a critical part of ESG goals. Organisations may choose to include this information in sustainability reports and/or report through one of the voluntary carbon focused schemes available (such as the CDP global disclosure system).

Given the range of mandatory and voluntary reporting schemes, it is important at the outset, to determine what type of data is to be collected and how it is to be managed to satisfy all reporting requirements and avoid duplication of effort or extensive re-purposing. Some aspects of these schemes are expanded in the following sections.

Meet climate change targets

Every organisation needs to commit to local, state, and national targets and goals for Australia to achieve its global commitment. This also means being prepared for review and strengthening of Australia's NDC at five-year intervals.

In addition, as stated above, all states and territories have committed to zero emissions by 2045 (ACT) or 2050, and some have adopted emissions reductions targets. The commitment to net zero has been legislated in the ACT and Victoria, and other states may follow (e.g. Tasmania). Local Councils have or may also adopt a similar goal. In effect, this means that Australia has a net zero emissions by 2050 goal.

Calculating its carbon footprint and developing an emissions inventory now can help an organisation prepare for future legislation.

Comply with NGER

The NGER scheme was established under the NGER Act 2007 and is administered by the Clean Energy Regulator (CER). All controlling corporations (obligations under the NGER Act apply to controlling corporations only) that meet set thresholds for GHG emissions and energy production or consumption under the scheme must apply to be registered under Section 12 of the NGER Act. The thresholds for facility and corporate group levels are provided below. The corporate group thresholds include historic obligations from past years (see CER).

Facility threshold:

· 25 kt or more of greenhouse gases (CO2-e) (scope 1 and scope 2 emissions)

· production or consumption of 100 TJ or more of energy.

Corporate group threshold:

· 50 kt or more of greenhouse gases (CO2-e) (scope 1 and scope 2 emissions)

· production or consumption of 200 TJ or more of energy.

A Scope 1 emission of greenhouse gas means the release of GHG into the atmosphere as a direct result of an activity or series of activities (including ancillary activities) that constitute the facility.

A Scope 2 emission of GHG means the release of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere as a direct result of one or more activities that generate electricity, heating, cooling or steam that is consumed by the facility but that do not form part of the facility.

Unregistered organisations should undertake due diligence to establish whether their activities trigger reporting under the NGER scheme and whether the Safeguard Mechanism applies.

The Safeguard Mechanism ensures that emissions reductions purchased through the Emissions Reduction Fund are not offset by significant increases in emissions above business-as-usual levels elsewhere in the economy. It does this by encouraging large businesses not to increase their emissions above historical levels.

Provide Assurance

The use of highly regarded standards (e.g. AS, ISO), programs (e.g. Climate Active Program, formerly The National Carbon Offset Standard (NCOS)) and recognised procedures (e.g. GHG Protocol) and disclosure platforms provide assurance about an organisation’s GHG emissions accounting results and management (including setting Science Based Targets). This is further strengthened by certification by a third party. It is expected that carbon risks are material issues for most companies for reporting purposes, notwithstanding the reduction targets and net zero emissions goals discussed above.

The obligation for businesses is underlined by a recent Supplementary Memorandum of Opinion (26 March 2019) by Mr Noel Hutley SC and Mr Sebastian Hartford Davis on “Climate Change and Director’s Duties” which included the following:

“There are, at the present time, significant and well-publicised risks associated with climate change and global warming that would be regarded by a Court as foreseeable”.

Affected sectors include banking, insurance, asset management, energy, transport, material/buildings, agriculture, food, and forest products.

Potential material risks apart from NGER non-compliance include the possibility of litigation from carbon pollution, rising costs (e.g. energy, environmental management) and the reinstatement of a price on carbon (note, the findings of a recent paper by Best et al (2020) were that carbon pricing works towards achieving a low carbon development model).

There are several standards and protocols available to give assurance to organisations for developing and maintaining their GHG inventories. For instance, AS ISO 14064 Greenhouse Gases Parts 1, 2 and 3 cover:

Principles and requirements for designing, developing, managing, and reporting organisation- or company-level GHG inventories

Principles and requirements for GHG projects or project-based activities designed to reduce GHG emissions or increase GHG removals

Principles and requirements for verifying GHG inventories and validating or verifying GHG projects.

This standard builds on the GHG Protocol, which published its first Corporate Standard in 2001 and is discussed further below.

The Climate Active Program is the Australian Government’s endorsed carbon neutral certification, which is underpinned by Climate Active Carbon Neutral Standards. To achieve certification, an entity (such as an organisation) must – measure emissions, reduce as much as possible, offset remaining emissions, then publicly report on its achievement. Certification allows businesses and organisations use of the Climate Active trade mark, helping consumers and the community to immediately identify products and services that are carbon neutral.

Developing an emissions inventory is the first step towards setting a science-based target (SBT) for emission reductions. The SBTi provides case studies outlining the why and what of setting a SBT, including the first SBTi endorsed Australian company, Origin Energy. Origin Energy developed this target to ‘get energy right for customers, communities, and the planet’ while helping them to demonstrate their leadership position on climate change. SBTs do not have to be approved but they can be submitted for review and listed as “Committed” in the Companies Taking Action page of the SBTi website.

Disclosure platforms or similar initiatives (such as sustainability reporting discussed in the following section) have been adopted and used by the sustainability community for some time. CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) runs the global disclosure system for investors, companies, cities, states, and regions to manage their environmental impacts. The listed benefits of disclosure for companies include – protected reputation, competitive advantage, identifying risks and opportunities and benchmarking. CDP tackles environmental risks throughout the supply chain.

More recently (June 2017), the sector-led Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) produced recommendations to develop voluntary consistent risk disclosures for use by companies to inform investors, lenders, insurers, and other stakeholders. This is a living document. The Task Force considers the physical, liability and transition risks associated with climate change and the recommendations help an organisation to describe in a voluntary, positive and consistent way how they think about climate risk and its possible impact on the way they do business. In July 2020, the Institute of Environmental Management & Assessment (IEMA) launched a guide specifically for users of climate related financial disclosure.

Report on sustainability

Developing and disclosing information about its carbon footprint using a voluntary reporting protocol provides many potential benefits to an organisation, including demonstrating its commitment to climate change action. Sustainability reporting can help organisations to measure, understand and communicate their economic, environmental, social and governance performance, set goals and manage change effectively. It is primarily non-financial in nature and therefore complementary to climate-related financial disclosures.

While there is focus on materiality and risk, sustainability reporting also provides a platform to share achievements towards minimising carbon footprint, innovating towards decarbonisation and benefits to society. Publicly sharing information on carbon management can assist the community to adapt to the worst impacts of climate change, by leading by example in climate change mitigation, and increase stakeholder trust.

The opportunity for working in partnerships is a key focus for sustainable organisations and development. One example of a partnership opportunity is the Aboriginal Carbon Foundation, which aims to build wealth for Traditional Custodians and non-Aboriginal carbon farmers, implementing carbon projects that demonstrate environmental, social and cultural core benefits, through the ethical trade of carbon credits.

Benefits internal to the organisation include the hiring and retaining of employees that are attracted to organisations with values aligned to their own. In their Employee Benefits Trends Study 2019, MetLife found that meaningful work or a sense of purpose tops the list for existing or potential employees (93%).

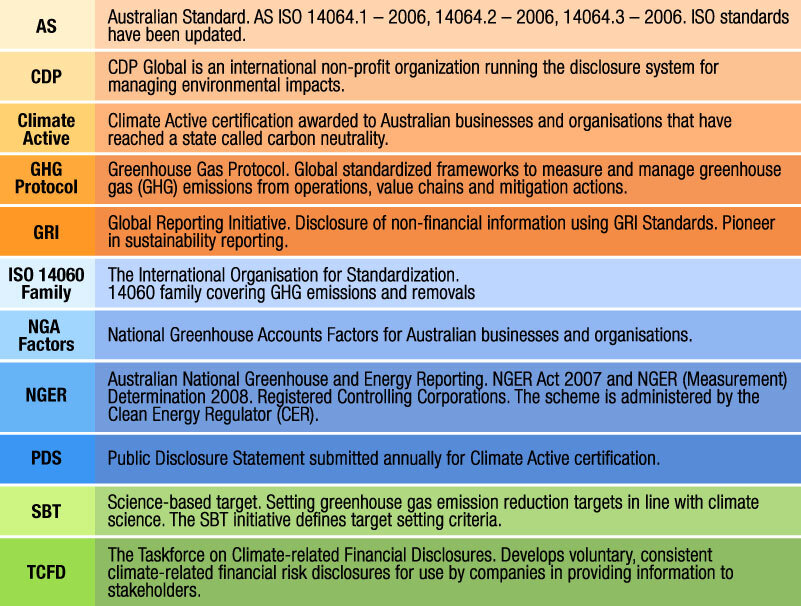

An overview of the GHG accounting and disclosure ecosystem for organisations

The image below describes the main actors in the accounting and disclosure ecosystem. Nodes are GHG emissions measurement standards, accounting methods and disclosure platforms. NGER is mandatory (M) in Australia for organisations exceeding thresholds. The figure shows yellow links (voluntary) between nodes, such as using the GHG protocol to prepare information for reporting on the CDP platform. Dashed lines indicate a relationship in development of the standard or method or where it refers to another protocol. ISO 14064.1 for example, is consistent with the GHG Protocol and the NGA Factors draw on the NGER (Measurement) Determination. In addition, the NGER scheme follows the GHG Protocol principles and guidance refers to this protocol for further information. The blue link shows that producing a PDS is a requirement of Climate Active (carbon neutral) certification. The Science-based Target aims for 1.5°C (one of two targets). These are not exhaustive, but illustrative of links found in online literature while producing this article for organisations.

Earth image courtesy of word stock. Mapping designed by Shelley Anderson.

Conclusion: From awareness to action – Building Back Better

Many recognised frameworks (mandatory and voluntary) are in place to support action from all business sectors towards Australia’s carbon reduction targets under the Paris Agreement and the global community achieving net zero emissions by the middle of the century. Responding to climate risk is a shared responsibility.

Some of these protocols were introduced around twenty years ago and are well established, but continue to evolve rapidly alongside recent approaches to embrace science-based targets (climate aligned metrics), achieve climate neutrality and publish public disclosures (including climate-related financial disclosures). These approaches do help an organisation to identify materiality, risk and opportunities in carbon management, and environmental management in general.

Organisations that choose to calculate and act on their carbon footprint now (if they are not already) will be better prepared for more stringent regulations and commitments or higher expectations from investors. This may require upskilling within the organisation to undertake the analyses required or overcoming barriers to data collation and management. Commitment from the organisation at the highest levels will help address these challenges. It is expected that large-scale firms will invest in monitoring, managing, and responding to climate change risks.

The next big challenge is refining techniques for measuring and reporting on Scope 3 emissions. There is public demand for transparency about the carbon footprint of products, particularly for upstream emissions from supply of raw materials. While few companies have managed to do this to date, new standards are emerging to satisfy this need.

Most of the schemes discussed in this article impose strict reporting requirements to maintain certification or recognition under the scheme. Verification, such as by independent audit, affords the organisation some protection against criticisms of greenwashing.

Australia can invest in the growth and employment potential of a low carbon economy. As demonstrated by this pandemic, the experience of having to change rapidly and without warning can make a society more open to other change. This provides the opportunity for impact focused management without limiting the extent of ‘building back better’ and to accelerate the transition to carbon neutrality. Net zero 2050 is a powerful roadmap for action.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

By Shelley Anderson, a freelance certified Environment Practitioner and Sustainability professional with experience in Australia and the UK. Her expertise includes pollution and fate, biodiversity creation, sustainability reporting, environmental risk management, and due diligence, across a broad range of market sectors. She was also a Director of the Cotswold Canals Trust (UK) where she applied her skills to charity governance and impact.

—————————————————————————————-

Click here to read about iSystain’s Sustainability and Carbon Reporting solutions module or contact us directly to speak to an iSystain consultant.