Creating and Applying Risk Appetite Statements

Introduction

The Good Governance Guide by the Governance Institute of Australia (GIA), describes the importance of risk appetite statements for organisations. It starts by saying - It is good governance for organisations to articulate and communicate their appetite for risk with a formal risk appetite statement, and that it provides a sound management foundation for risk management. However, it also offers a warning: if there is a lack of shared understanding of risk appetite between the board and management then a culture develops that suffers from misunderstandings about risk in decision-making.

Commentary by Alex Welng 2021 (Resilience Outcomes) echoes this warning that poorly structured risk appetite statements may not communicate what risks organisations are willing to live with and which ones they aren’t, which leads to poor decision-making. Webling provides a worst-case scenario where an organisation states that it has a ‘zero tolerance’ for an activity but due to miscommunication, still undertakes that activity.

The point here is that structured risk appetite statements are important for building an organisation’s risk culture and enabling decision-making, but only if the risk statements are properly communicated by the peak governing mechanism, understood by management, and utilised within the risk management framework.

Information about how to articulate risk appetite statements (RAS) is available from numerous sources including the GIA, Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) and Comcover (the Australian Government's self-managed insurance fund who provide information sheets and case studies), while ISO Guide 73:2009 provides risk management definitions (including for risk appetite).

This article reviews the basics of risk appetite statements (RAS), the benefits to an organisation, and what is necessary to ensure it is properly communicated and implemented – such that scenarios, as outlined above, are rare occurrences. It also reflects on the findings of the Northern Australian Committee led enquiry into the destruction of the Juukan Gorge caves in 2020, in the context of risk review.

What is your organisation’s risk appetite?

The AICD acknowledges that all organisations need to take risks to increase value, productivity, and perhaps even sustainability, but the question arises of how much and what types of risks should they take? The AICD also reminds us it is the board’s (or other peak governing mechanism such as senior management’s) role to set and communicate the risk appetite of the organisation, such that it is understood and implemented by operational management through its risk management framework.

Comcover offers a similar definition: the amount of risk an organisation is willing to accept or retain to achieve its objectives, which in turn aids decision-making. Managers can compare their organisation’s risk exposure (evaluated through the risk assessment process) with the organisation’s risk appetite (as set by the board/senior management) to ensure they are maintaining the right level of risk. The implementation of these processes guides the risk culture of an organisation.

The benefits of defining an organisation’s risk appetite as discussed by Comcover include:

Supporting conscious and informed risk-taking (e.g., new programs, efficiency initiatives, reduced delays, innovation)

Promoting consistent risk management

Guiding risk decision making and seizing opportunities (e.g., increased transparency, opportunities for further risk-taking or areas where risk-taking is unacceptable)

Structuring the peak governance conversation on risk-taking, which encourages debate on what is desirable, acceptable, and unacceptable risk (note: the risk appetite levels are typically tailored to the organisation)

Calibrating the risk assessment process to ensure that severity risk levels (i.e., resulting from likelihood and consequence) are aligned with risk capacity and tolerance.

Risk appetite statements (RAS)

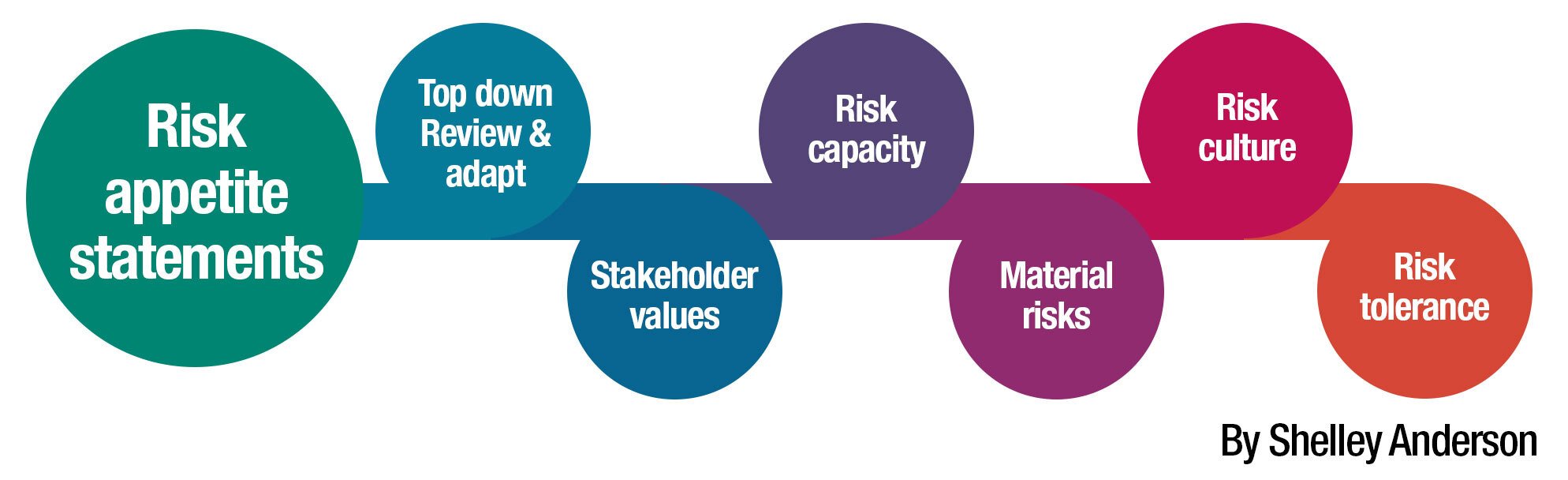

Boards and senior management typically set the risk appetite for a company when considering strategy and business plans as the two are often intertwined. Before discussing in further detail, the following terminology is useful to understand how risk appetite statements are developed and used. This is a summary of key terms as defined in ISO Guide 73: 2009 (Risk Management – Vocabulary):

Risk appetite: amount and type of risk that an organisation is willing to pursue or retain

Risk tolerance: an organisation's or stakeholder's readiness to bear the risk after risk treatment in order to achieve its objectives. Risk tolerance can be influenced by legal or regulatory requirements

Risk treatment: process to modify risk, which can include avoiding the risk, taking or increasing risk (to pursue an opportunity), removing the risk source, changing the likelihood or consequence, sharing the risk or retaining the risk by informed decision.

Risk appetite statements (RAS) therefore, communicate the board’s (or senior management’s) endorsement of, and attitude to, risk-taking and acceptance, how the information in the document is to be used, and a series of risk tolerance (e.g., low, medium, high) statements for relevant risk categories.

Some examples of risk appetite statements across several sectors and with different approaches to risk tolerance are provided here:

Setting & applying risk appetite

Setting risk appetite is a task that requires the balancing of many stakeholder values. While risk categories are tailored to the business, internal and external stakeholder views will vary. In addition, different functional units within an organisation may have different risk appetites.

To start with, it is useful to define an organisation’s risk capacity, which is the maximum amount of risk that a company can absorb in the pursuit of business objectives (TCFD 2020). It follows that risk appetites are set within the boundaries of risk capacity.

The key steps for setting risk appetite are to:

Define it at the board or senior management level based on a company’s core values, strategic plan and stakeholder values (or their own risk appetites). This could be aligned with organisational strategy as discussed in this previous blog:

o compliance by operating legally

o assurance by being proactive

o sustainability by focusing on material topics, or

o maximising positive impact

Consider the types of risks the company needs to take or avoid towards achieving its strategic ambition. These risks may already be defined within the risk management framework and/or materiality analysis. Common risk types include strategic, financial, operational, regulatory and compliance, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) and climate change. There will also be sub-risks within each of these categories

Tailor the risk categories to the business context. For example, some organisations may define health and safety risks at the category level, while others may include it as a sub-risk under the operational category. Similarly, ESG and climate change may be included as sub-risks under environment but there is sufficient scrutiny and stakeholder demand now to warrant individual attention

Describe the risk tolerance within each category (quantitative or qualitative) such that the organisation’s risk capacity is not exceeded. If tolerance is quantitative, such as for a financial institution, then this step might comprise an allocation to each category from a total amount of risk

Utilise stress testing and scenario analysis to test risk tolerance, where applicable (e.g., climate-related impacts under the TCFD)

Ensure that management is assuming sufficient risk to identify new growth opportunities.

Considerations for an organisation applying risk appetite include to:

Adopt risk appetite as a proactive expression by the board or senior management of their direction for the organisation (risk culture)

Avoid risks that, after considering the impact of risk treatment, are outside its risk appetite (whether that be high tolerance or low tolerance)

Undertake risk monitoring and reporting at the appropriate organisational level (e.g., office-wide level rather than individual office) to ensure that identified risks remain within its risk appetite, including zero tolerance risks

Review risk appetite and risk management framework – it’s an evolving landscape depending on the status of issues or the organisation’s risk position, risk treatment success or risk response, emerging issues and knowledge, and interactions with other risk appetites.

Monitoring and review

Risk appetite and tolerance should be reviewed any time there are material changes in strategy or market conditions. It is an iterative process as the board/senior management and operational management become more familiar with risks and opportunities and how those issues impact strategic objectives. It can also be a dynamic process, allowing adjustment of risk appetite as new skills are added to develop products and services.

Sectors with mature risk evaluation skill sets are proactive towards recognising contemporary and emerging risks. In the resources sector, for example, Gold Road has an established Risk and ESG Committee that annually reviews its operations against its risk appetite set by the board and considers new risks such as conduct risk, technology and innovation (e.g., cyber-security, privacy, and data breaches), sustainability, cultural heritage and climate change risks.

However, certain types of risks, such as climate change, are developing at high velocity on the one hand, but over long-time horizons on the other. The TCFD (2020) in its Guidance on Risk Management Integration and Disclosure asks companies to describe climate-related risks over the short, medium, and long-term to make sure it is sufficient to take account of the range of climate-related risks.

To ensure good decision-making, it is also important for organisations to gather sufficient indicator data to warn of a pending breach of risk appetite limits, such that preventive action can be undertaken. It might be necessary to decelerate or accelerate growth to meet risk tolerance levels, for example. However, risk managers need to demonstrate understanding across all categories to ensure achieving one objective does not expose the organisation to risk in another.

A high profile case study for risk review

Australians and the world were shocked by the destruction of 46,000+-year-old caves in the Juukan Gorge (Pilbara region, Western Australia) by Rio Tinto on 24 May 2020 - even though this destruction was permitted under the Western Australian (WA) Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972.

The Northern Australian Committee led the inquiry into this destruction and tabled its final report, A Way Forward, on 18 October 2021. The inquiry and review found the destruction caused immeasurable cultural and spiritual loss, as well as profound grief for the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura peoples (PKKP), and that Rio Tinto’s actions demonstrated the profound lack of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage in this country.

This report reminds us of the importance of monitoring evolving risks and/or the changes in stakeholder values, including in response to cultural understanding and scientific knowledge over time. Within its summary of events, the review acknowledged there were significant gaps between three key chronological points:

the consent in December 2013 for impacts at the Juukan 1 and Juukan 2 rockshelters

the increased understanding of the exceptional significance of the site arising from the salvage operations in 2014

the timing of the impacts in May 2020.

The report states that during that period risks should have been reviewed and updated regularly. The view that active management of the site - post consent and artefact salvage - was no longer necessary neglected the reality that:

such sites are not necessarily ‘low risk’, and

there are situations in which cultural heritage issues evolve in ways that require them to be reassessed.

It could be argued that a low-risk appetite, which accepts as little risk as possible, engenders a cautious approach, and triggers continuous review and reporting to the Board, could have helped protect this cultural heritage.

Conclusions

Risk appetite is a structured statement (or series of statements) that articulates an organisation’s willingness to seek, accept and/or tolerate risk to achieve its objectives. This structure enables effective decision-making but requires an active risk management framework and regular review of risk exposure. The risk appetite statement should consider preventive measures for risks to operations and strategic plans and proactive measures to develop opportunities for increasing business value.

A lack of reporting of leading risk indicators, with appropriate metrics compared to risk appetite and tolerance, means that risk may not be adequately monitored at peak governing level and result in failure by the organisation to adapt to new and different operating environments. Evolving or emerging issues (such as cultural heritage and climate risk) may be on the agenda, but risk and governance maturity around these issues could be low.

As stakeholder expectations for transparency and disclosure continue to increase, we can expect to see more publicly available risk appetite statements, thereby heightening understanding of the major issues challenging business and society today.

Shelley Anderson is a freelance Certified Environment Practitioner and sustainability professional with experience in Australia and the UK. Her expertise includes environmental risk assessment and management, due diligence, and reporting across a broad range of industry sectors. Shelley was also a Director of the Cotswold Canals Trust (UK) where she led the Natural Environment team and applied her skills to charity governance and impact.

Written in consultation with Jenni Mulligan, Co-Founder and a Principal Consultant @ iSystain .

—————————————————————————————-

Click here to read about iSystain’s Risk management solution or contact us directly to organise a consultation with an iSystain consultant.