Mainstreaming Biodiversity Values for Business

Understanding your business’s impact on biodiversity and its impact on you

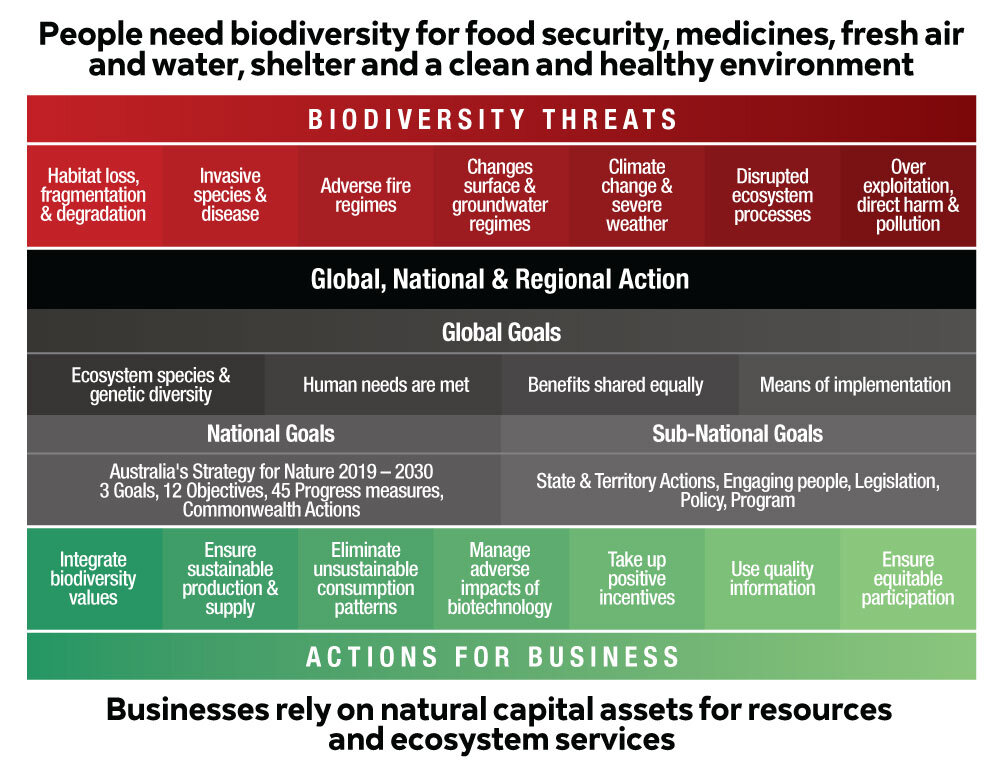

All public and private businesses of all sizes need to assess and report on their dependencies and impacts on biodiversity from local to global scales. While the effects of biodiversity loss on a business’s activities might not be immediately apparent, delving into its supply chain will show where those links are…think natur(e)al resources.

September marks Biodiversity Month in Australia. We explore what biodiversity means, and why, like climate change, action must be taken this decade to halt the decline.

The state of decline

Biodiversity loss is increasing, despite international and national efforts to achieve targets set for 2020 under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). As such, we have been aware of the human dimension of this crisis for some time - it was in a 2008 scientific article by Wake and Vredenburg, that the phrase “sixth great mass extinction”, articulated the impacts of human pressure on natural environments.

We know the biodiversity crisis cannot be solved in isolation. While we aim for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 14: Life Below Water and 15: Life Below Land by 2030, these goals inherently affect others, including Goal 2 on ‘zero hunger’ (food security and nutrition) and Goal 12 for responsible consumption and production. We are now also recognising the interrelationships between climate and biodiversity with the world’s first collaboration between the intergovernmental body tasked with assessing the science related to climate change (the IPCC) and the body tasked with the state of biodiversity and ecosystem services (the IPBES). These interrelationships include the role and implementation of nature-based solutions and the sustainable development of human society.

Such global frameworks remind us that humans are part of a complex ecosystem and that human-driven changes are having a significant effect on this system. Closer to home, the independent reviewer of Australia’s Environment Protection & Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act 1999), Professor Graeme Samuel, found that Australia’s natural environment and iconic places are in an overall state of decline and are under increasing threat. They are not sufficiently resilient to withstand current, emerging or future threats, including climate change.

Our quality of life is intertwined with nature

According to the Australian Museum, biodiversity comes from bio meaning life and diversity meaning variability. Biodiversity is the variety of all living things: plants, animals, and microorganisms, the genetic information they contain and the ecosystems they form. Genetic diversity, species diversity and ecosystem diversity work together to create the complexity of life on earth. Similarly, under the EPBC Act 1999, components of biodiversity comprise species, habitats, ecological communities, genes, ecosystems, and ecological processes.

Allowing the decline of our natural environment directly impacts on human health and wellbeing. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) mentioned above, is an international treaty agreed to at the UN Earth Summit in Brazil in 1992 and ratified by Australia in 1993.

It recognises that “biological diversity is about more than plants, animals and microorganisms and their ecosystems – it is about people and our need for food security, medicines, fresh air and water, shelter, and a clean and healthy environment in which to live”.

Failure to meet 2020 targets

Countries had until 2020 to achieve the twenty Aichi Biodiversity Targets, adopted as part of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011 – 2020, but none of these targets were achieved.

However, despite the overall poor outcome, six targets have been partially achieved and progress has been made in ten areas – natural accounting, deforestation, fisheries management, invasive alien species on islands, protected area estate, extinctions, genetic resources, access to information and financial resources.

The post-2020 global biodiversity framework

The post-2020 global biodiversity framework is expected to be adopted at the United Nations (UN) Biodiversity Conference in Kunming China later this year (11 to 24 October 2021). The vision of this new framework is a world of living in harmony with nature where: “By 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people.”

The framework comprises four long-term goals for 2050, eight milestones to assess progress in 2030 and 20 action-oriented targets for 2030. Many of the action targets are quantitative, with measures around per cent conservation (e.g., protect and conserve at least 30% of the planet) and per cent reduction in threats such as the introduction of invasive alien species and excess nutrients, biocides and plastic waste.

Accounting for nature-negative outcomes

The World Economic Forum (WEF) in its New Nature Economy (NNE) report estimates that more than half of the world’s economic output – $44 trillion of economic value generation – is moderately or highly dependent on nature. The three largest sectors that are highly dependent are construction, agriculture and food and beverages, which together generate close to $8 trillion of gross value added (GVA).

These figures frame the double materiality of biodiversity loss which considers both impact and financials:

(1) impact materiality, which is the negative or positive impact of business operations and its value chain on people and the environment (e.g., biodiversity loss or gain); and

(2) financial materiality, which is the impact (e.g., of biodiversity loss) on the value of the company.

An article by Corrs Chambers Westgarth sums up this concept, explaining “how the corporation depends on biodiversity and how that corporation impacts biodiversity”. Nature loss matters for most businesses through impacts on operations, supply chains, and markets, and exposure to reputation, legal and financial risks.

To counteract biodiversity loss, there is a growing level of support for economic language and frameworks to describe nature’s contribution to local and national economies, such as ecosystem services, natural capital, and natural accounting. These approaches posit that putting a dollar value on nature will give governments and businesses more reasons to protect it. However, others argue that reconnection with nature is the best way to solve our current environmental crises.

Recognition of these issues has also driven an industry-led initiative to develop the Taskforce for Nature-related Disclosures (TFND), which is expected to be launched in 2023. This taskforce will build on the TFCD (climate-related disclosures) to cover nature-related risks excluded through the climate lens. Both frameworks have the effect of shifting global financial flows away from negative impacts towards nature-positive outcomes and opportunities.

Enduring threats to Australia’s biodiversity

Recently published research by Ward et al, June 2021 is the first complete threat and impact dataset for all nationally listed threatened taxa (groups) in Australia. It evaluates eight broad-level threats and 51 subcategory threats for the 1,795 threatened terrestrial and aquatic taxa.

The dataset shows the most at-risk groups in Australia are plants, comprising 74.6 % of all threatened taxa while 27.7 % of mammals (386 taxa) are listed as threatened. Contributing to this are the most frequently listed threats being habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation (affecting 1,210 taxa), invasive species and diseases (affecting 966 taxa), and adverse fire regimes (683 taxa).

The authors conclude that mitigating against these threats, along with adaptation to climate change, is crucial for curbing species decline. Whilst the top three threats inform prioritisation of conservation efforts (including under the EPBC Act), the other five broad-level threats remain important - changed surface and groundwater regimes, climate change and severe weather, disrupted ecosystem and population processes, overexploitation and other direct harm from human activities and pollution.

Mainstreaming biodiversity values for business

Biodiversity impacts are not limited to large-scale operations comprising land clearing, extractive industry, or water abstraction – many of which are mitigated through the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process. Understanding an organisation’s value chain is integral to sustainability (see our blog on Supply Chains), whether it be for mitigating environmental (e.g., biodiversity) or social (e.g., modern slavery) risks.

The research undertaken by Ward et al (2021) provides a dataset for prioritising efforts in Australia in terms of biological taxa, but attention also needs to be given to the human elements, such as under served or remote communities that are directly impacted by the loss of nature. The extraction of groundwater in a community that relies on groundwater for drinking, for example. Furthermore, supply chains may extend globally - including to developing countries - where the negative impacts on workers and local communities along the chain are increasingly scrutinised.

Steps businesses can take to mainstream biodiversity values - by applying the draft post-2020 global biodiversity framework - are discussed below.

Integrate biodiversity values into strategies, policies, and environmental assessment and management. The mining industry has developed policies and environmental management and rehabilitation procedures linked to Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and development conditions, but this is less visible for other sectors. For examples of rehabilitation areas, Gold Road, reported 106 ha of area disturbed in 2020 against 211 ha rehabilitated. On a larger scale, Glencore Coal Mine Rehabilitation (2021 Update) reported 1,382 ha of rehabilitation completed with 794 ha across Queensland and New South Wales certified.

One organisation who has acknowledged Biodiversity Month is ANL – a shipping and logistics company within the CMA CGM Group, whose core principles include the sustainable use of the oceans and respect for marine life. ANL has partnered with the Reef Restoration Foundation to establish a fast-growing coral nursery off the coast of Queensland to produce mature coral to place back on the Great Barrier Reef (the Reef Recovery Program).

Ensure production practices and supply chains are sustainable: the draft post-2020 biodiversity framework has an action target of at least 50% reduction in negative impacts on biodiversity through supply chains. Corporate Citizenship provides case studies addressing some of these issues, such as a new Palm Oil Charter by the Ferrero Group – featuring commitments to regenerate biodiversity, soils and water systems - and the establishment of the PlenaMata portal via a partnership with Natura & Co, which gathers data and indicators used in conservation and regeneration of the Amazon biome.

Eliminate unsustainable consumption patterns: Mirvac for example, recognises that its industry relies on finite natural resources to construct and operate buildings, which ultimately impacts on biodiversity, and has committed to net positive water and zero waste to landfill by 2030. Other initiatives include switching to renewable energy or engaging with sustainable food producers.

Manage the potential adverse impacts of biotechnology: by applying environmental and human health risk assessment and Biotechnology Code of Ethics. Some biotechnology companies have sustainability embedded, such as Pacific Bio, which has developed technology using microalgae to remove nutrients from wastewater, which is then further developed into nutrient supplements.

Take up positive incentives for biodiversity – according to Bishop (2020), Australia has good experience using market-based environmental incentives including carbon offsets, biodiversity offsets, and water buybacks and reef credits. Natural resource user fees can also be used to raise revenue for protected areas and eco-tourism operations.

Use quality information to inform decisions, including traditional knowledge. Australia’s Nature Hub compiles actions undertaken towards our National Goals. The Our Knowledge Our Way Guidelines (2020) are the first Indigenous-led, co-developed attempt to guide a new paradigm for how Indigenous knowledge is engaged in Australia.

Ensure equitable participation in decision-making and ensure the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities, women and girls and youth. For example, the Ferrero Group’s Palm Oil Charter includes commitments to create positive carbon and biodiversity impacts, foster the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities during land acquisition, and require equal pay for equal work for women.

Leading the way with data

Australia’s Sixth National Report on implementation of the CBD 2011 – 2020 biodiversity framework found that it was not possible to report on the achievement of the interim national targets because of insufficient national-scale data to assess progress. Furthermore, one of the lessons learned from the global experience of the last decade is the need for well-designed goals and targets formulated with clear language and with quantitative elements.

Samuel (2020), in his review report on the EPBC Act 1999, dedicates a whole chapter (Chapter 10) to data, information and systems, including flagging the lack of official data and key reforms. Reforms include a national supply chain of information that improves over time and a National Environmental Standard (NES) for data and information to improve accountability and provide clarity on expectations. Unfortunately, there has been no indication of uptake of information supply chain by the Commonwealth Government to date, although a previous commitment to a Digital Assessment Program may go someway to providing consolidated sources, and some Interim NES will be introduced.

Nonetheless, businesses need to formulate their biodiversity plans with metrics and targets that can aggregate up to inform sub-national, national, and global frameworks, as well as their own nature-related financial disclosures. Alignment of Australia’s biodiversity policy (including the Interim NES) with the post-2020 framework should lead to consistent and standardised data reporting.

Again, complementary approaches are being adopted for climate and nature stabilisation with the introduction of the science-based targets (SBTs) network – which is working to enable companies to set targets based on the best available science and align with Earth’s limits and societal sustainability goals.

The transformation towards sustainability and protecting or enhancing biodiversity is compatible with business goals, since all businesses depend on biodiversity in some way. It is urgent: the world failed in its 2020 targets but is resetting for 2030 milestones, and coordinating with climate change action. However, like climate change, we need to move beyond neutrality to positive impacts, so that we and nature thrive.

Shelley Anderson is a freelance Certified Environment Practitioner and sustainability professional with experience in Australia and the UK. Her expertise includes environmental risk assessment and management, due diligence, and reporting across a broad range of industry sectors. Shelley was also a Director of the Cotswold Canals Trust (UK) where she led the Natural Environment team and applied her skills to charity governance and impact.

Written in consultation with Jenni Mulligan, Co-Founder and a Principal Consultant @ iSystain .

—————————————————————————————-

Click here to read about iSystain’s Sustainability Reporting solution or contact us directly to organise a consultation with an iSystain consultant.